Introduction¶

Introduction to SFINCS¶

What is SFINCS?¶

SFINCS (Super-Fast Inundation of CoastS) is a reduced-complexity model capable of simulating compound flooding with a high computational efficiency balanced with an adequate accuracy. In SFINCS a set of momentum and continuity equations are solved with a first order explicit scheme based on Bates et al. (2010). Traditionally SFINCS neglects the advection term (SFINCS-LIE) which generally justified for sub-critical flow conditions. For super-critical flow conditions or when modelling waves, the advection term needs to be solved. For this purpose, the SFINCS-SSWE version can be used (including advection). For more information see Leijnse et al. (2020): https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coastaleng.2020.103796

Why SFINCS?¶

Compound flooding during tropical cyclones and other extreme events result in tremendous amounts of property damage and loss of life. Early warning systems and multi-hazard risk analysis can reduce these impacts. However, large numbers of computations need to be run in a probabilistic approach and in a short time due to uncertainties in the meteorological forcing. Current modelling approaches are either fast but too simple (bathtub approach) or models are very accurate but too slow (e.g. Delft3D, XBeach). SFINCS balances a high computational efficiency with adequate accuracy. Therefore the model is very appropriate to either to model a large stochastic set of scenarios, run the same model on a higher resolution or model larger scales. Thereby, one can use it as a quickscan tool to quickly test possible adaptation and mitigation measures to flooding. The scope of the model is therefore different than other models in Deltares’ modelling suite. When very high-detailed simulations are needed with a lot of detailed features (or including morphology, salinity etc.), one can use the Delft3D FM Suite, see: https://www.deltares.nl/en/software/delft3d-flexible-mesh-suite/

Fig. 1 The goal of SFINCS: speed! (Icon made by https://www.flaticon.com/authors/vectors-market)¶

Compound flooding?¶

Compound flooding is described as events occurring in coastal areas where the interaction of high sea levels, large river discharges and local precipitation causes (extreme) flooding (Wahl et al., 2015). To simulate compound flooding events, a model needs to be able to model all these types of forcings. Therefore, SFINCS includes fluvial, pluvial, tidal, wind- and wave-driven processes!

Application areas¶

Coastal model¶

A SFINCS model in coastal regions can be forced with marine forcings like tides, storm surge, local wind setup and wave driven processes. Generally a model is setup with the offshore boundary in the swash zone, good practice is in about 2 meters water depth. In SFINCS it is possible to distinguish cells that are made inactive in the computation so it will not slow your model down (in this case everywhere deeper than 2m water depth). In some cases local rainfall might be relevant too for a coastal model.

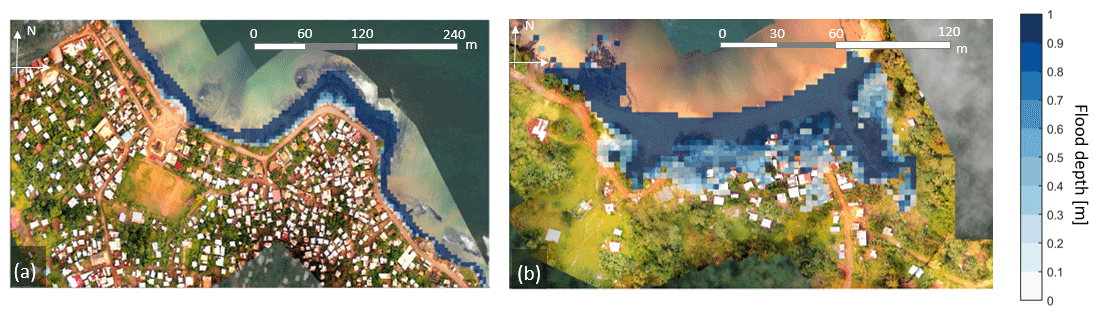

Fig. 2 SFINCS model for Sao Tome en Principe, figure from: https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-20-2397-2020¶

Coral reef model¶

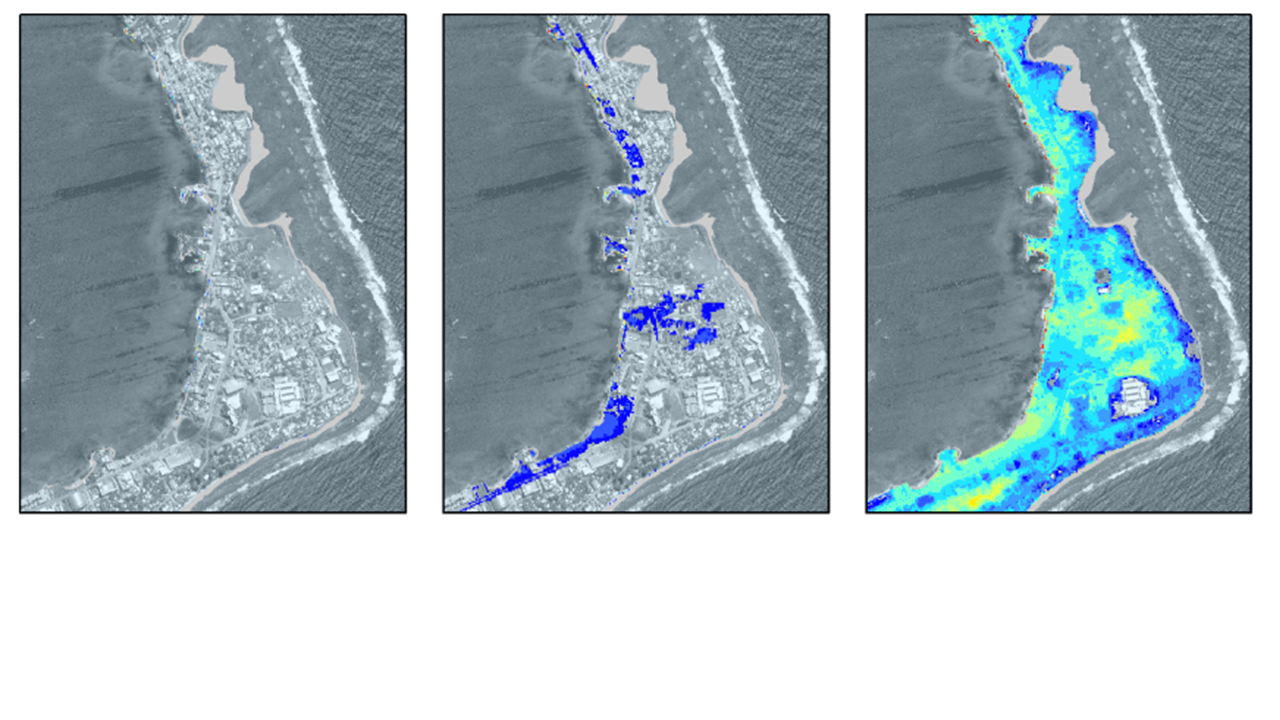

SFINCS models have also been setup in coral reef type environments, where individual waves are forced to compute wave-driven flooding. This generally has a large contribution to flooding for Small Island Developping States (SIDS) or other coasts/islands with coral reef type coasts.

Fig. 3 SFINCS model for Majuro.¶

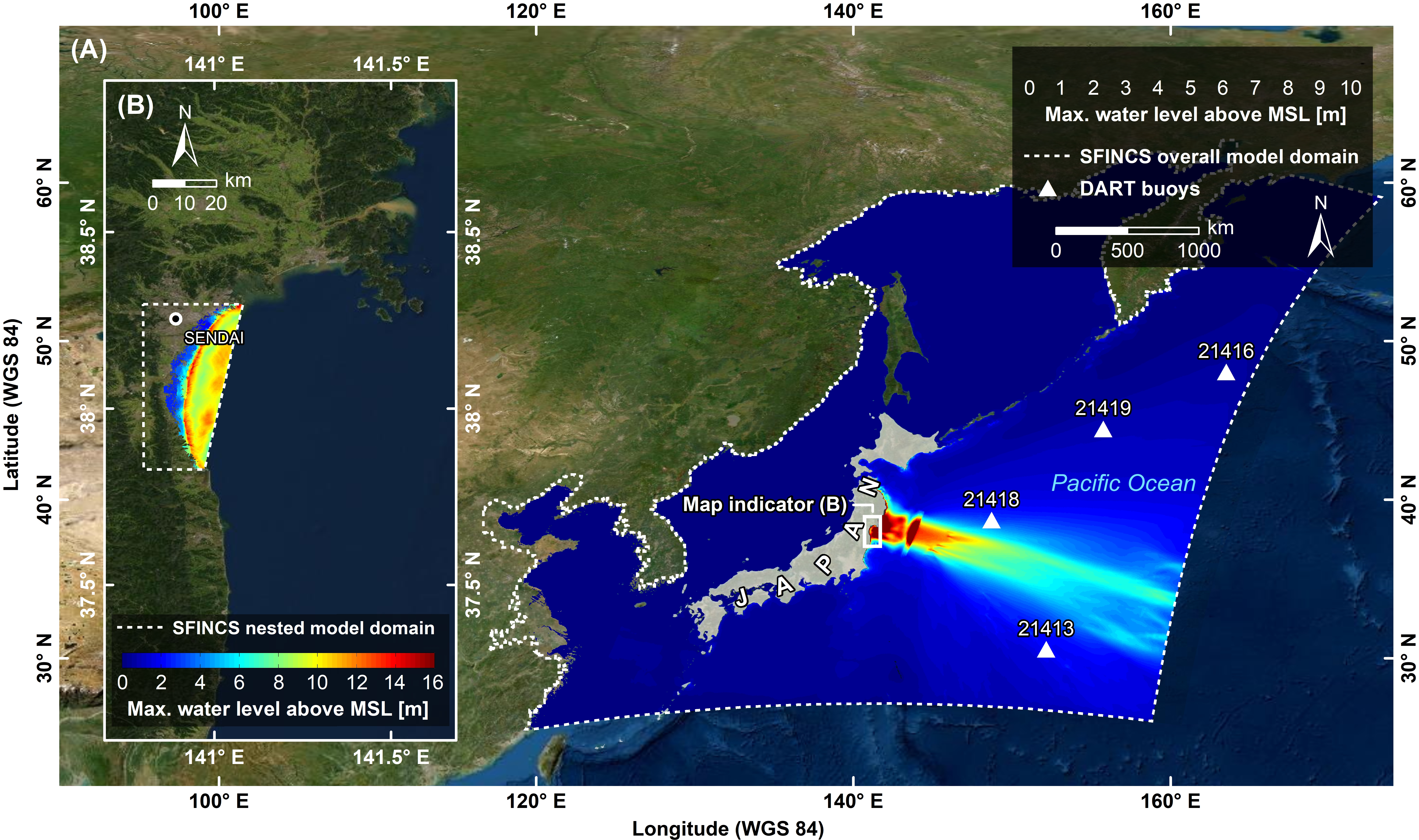

Tsunami model¶

As an additional type of coastal model, SFINCS has also been used for modelling tsunami’s. Generally this would be an overland model forced with a tsunami wave as computed by an offshore hydrodynamic model. However, in the paper of Robke et al. 2021 SFINCS was also used for the first time to calculate the offshore propagation in a very short amount of time too. Get in touch to hear more about possibilities for tsunami modelling with SFINCS.

Fig. 4 Overland and offshore SFINCS models modelling the 2011 Tohoku tsunami near Japan, figure from: https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse9050453¶

Storm surge model¶

Since speed is wanted everywhere, also tests have been done to let SFINCS model offshore storm surge during tropical cyclones. Get in touch to hear more about possibilities for storm surge modelling with SFINCS.

Riverine model¶

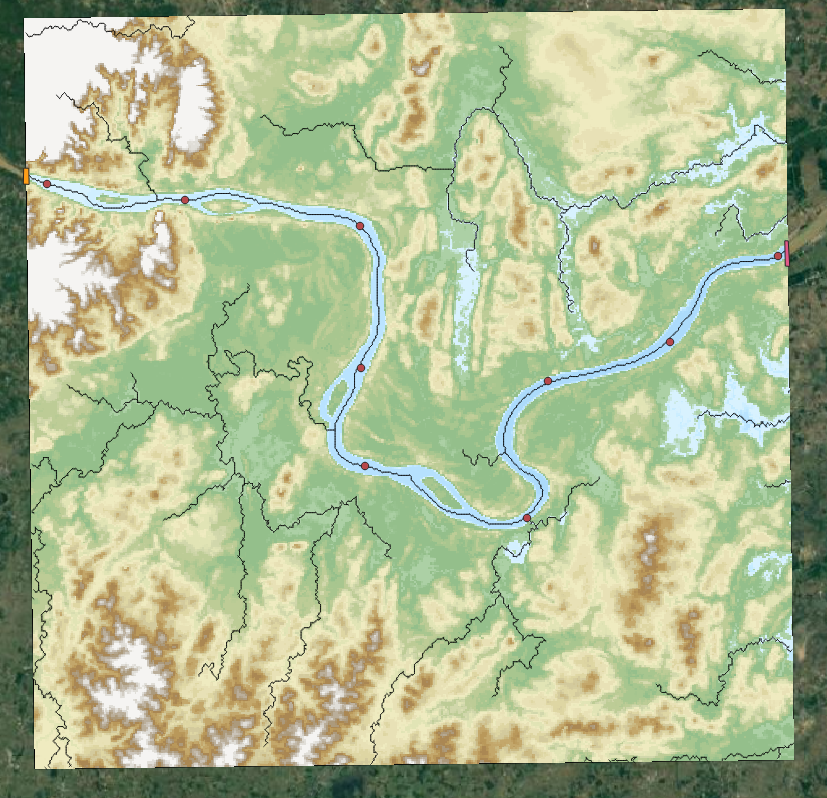

For inland riverine types of environments, boundary conditions are generally different than for coastal models. Generally at the upstream end of rivers, one can provide discharge points with discharge time-series. At the downstream end of rivers, water level time-series need to be specified, which in case of sub-critical flow conditions will influence the flow upstream. Additionaly, besides the general river discharge, local rainfall adding water to the river can be very relevant too.

Fig. 5 SFINCS model for Vientiane, Laos.¶

Urban model¶

For urban environments the local situation of varying land use conditions can heavily influence the local flow. Therefore spatially varying input of manning roughness and infiltration is possible. The curve number method of infiltration will distinguish what part of falling precipitation can infiltrate or will run-off. To test out the effect of interventions, it is possible to insert different types of structures into the SFINCS model. These can be thin dams, levees, sea walls, simple drainage pumps or culverts.

Fig. 6 SFINCS model for Houston, TX, during Hurricane Harvey (2017)¶

Flash flood model¶

In recent tests, SFINCS has also been used to model flash floods. In these events, a short but intense rainfall event falls onto a domain and together with a steep profile can lead to significant water depths and flow velocities. Get in touch to hear more about possibilities for fast flash-flood modelling with SFINCS.

Fig. 7 SFINCS model for Izmir, Turkey¶

Compound flooding model¶

In a compound flooding model, all relevant types of forcing from either coastal, coral, riverine or urban models can be combined into 1 domain. Hereby the joint effect of multiple flood drivers that can enhance flooding can be taken into account.

Fig. 8 SFINCS model for Jacksonville, FL, during Hurricane Irma (2017), figure from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coastaleng.2020.103796¶

Applied international projects¶

SFINCS has been applied in these international projects, with attached links to news articles:

Modelling of urban flooding and adaptation measures in the USA (https://www.deltares.nl/en/news/development-community-oriented-decision-support-tool-compound-flood-events-us/)

Modelling coastal driven flooding at Beira, Mozambique (https://www.deltares.nl/en/news/dutch-mozambican-consortium-to-protect-beira-against-coastal-flooding/)

Modelling sea level rise and storm driven flooding at 18 countries in the Caribbean (https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/36417)

Modelling multi-hazard driven flooding for the atoll of Majuro in the Marshall islands (https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/8c715dcc5781421ebff46f35ef34a04d)

Modelling compound flooding along the whole US Southeast coast (https://www.deltares.nl/app/uploads/2021/10/RD-Highlights-2021.pdf)

Modelling coastal flooding for the entire country of Denmark by the Danish Coastal Authority for the EU Floods Directive (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TbzTC82ijyU&t=15s&ab_channel=Deltares) (https://specials.deltares.nl/impact_report_2023/estimating_flood_impacts)

Fig. 9 Overview of countries globally where SFINCS has been used, including all SIDS¶

SFINCS has been applied (or still is) in multiple other international projects:

Modelling compound flooding for the islands of Sao Tome en Principe

Modelling tropical cyclone and sea level rise driven flooding in polders of Bangladesh

Modelling compound flooding at Monrovia, Liberia

Modelling sea level rise driven flooding at all the islands of the Marshall Islands

Modelling wave and groundwater -driven flooding across the Puget Sound, US West coast

Modelling wave-driven flooding at Miami, Florida

Modelling urban flooding in 100 global cities

Modelling sea level rise and storm driven flooding for all SIDS globally

Modelling coastal and riverine flooding in Denmark

Modelling wave-driven flooding in Cuba

Modelling flash-floods in Turkey

Modelling large scale compound flooding in Australia in a Delft-FEWS early warning system

Modelling wave-driven flooding on coral reeflined coasts of Puerto Rico

Modelling coastal and riverine flooding in Indonesia

Modelling wave-driven flooding in the Philippines

Modelling of urban flooding and adaptation measures in Ireland

Modelling emergency response of flooding in Pakistan and Nigeria during the 2022 floods

Modelling the impact of climate change mitigation strategies in Egypt

Modelling the 2023 dambreak in Libya (AXA Climate)

Modelling flood risk for the Bahamas

And many more!

Publications¶

There have been various journal publications and conference posters where SFINCS has been used and/or validated:

Introduction paper of SFINCS: “Modeling compound flooding in coastal systems using a computationally efficient reduced-physics solver: including fluvial, pluvial, tidal, wind- and wave-driven processes”. Leijnse et al. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coastaleng.2020.103796.

“Uncertainties in coastal flood risk assessments in small island developing states” - Parodi et al. (2020) https://nhess.copernicus.org/articles/20/2397/2020/

“Hindcast of Pluvial, Fluvial, and Coastal Flood Damage in Houston, Texas during Hurricane Harvey (2017) using SFINCS”. Sebastian et al. (2021). Sebastian et al. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-021-04922-3

“Rapid Assessment of Tsnuami offshore propagation and Inundation with D-FLOW Flexible Mesh and SFINCS for the 2011 Tohoku Tsunami in Japan”: Röbke et al. (2021) https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse9050453

“Efficient and accurate modeling of wave-driven flooding on coral reef-lined coasts: Case Study of Majuro Atoll, Republic of the Marshall Islands”. Bertoncelj et al. (2021). https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-egu21-5418

“Multilevel multifidelity Monte Carlo methods for assessing coastal flood risk”. Clare et al. (2022) https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-22-2491-2022

“A globally-applicable framework for compound flood hazard modeling”. Eilander et al. (2022) https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-2022-149

“Developing large scale and fast compound flood models for Australian coastlines”. Leijnse et al. (2022). ‘International Conference on Coastal Engineering 2022, Sydney’. https://doi.org/10.9753/icce.v37.management.49.

“Developing a real-time data and modelling framework for operational flood inundation forecasting in Australia”. De Kleermaeker et al. (2022). https://search.informit.org/doi/abs/10.3316/informit.916755150845355

“Flooding at the Fringe: A Reduced-physics Model for Assessing Compound Flooding from Pluvial, Fluvial, and Coastal Hazards”. Grimley et al. (2022). https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2022AGUFMNH36A..03G/abstract

“Large-Scale Operational Forecasting with the Compound Flood Model SFINCS”. Van Ormondt et al. (2022). In Fall Meeting 2022. AGU.

“Tropical cyclones or extratropical storms: What drives the compound flood hazard, impact and risk for the US Southeast Atlantic coast?” Nederhoff et al. (2023). https://eartharxiv.org/repository/view/5123/.

“Dynamic modeling of coastal compound flooding hazards due to tides, extratropical storms, waves, and sea-level rise: a case study in the Salish Sea, Washington (USA)”. Nederhoff et al. (2023). https://eartharxiv.org/repository/view/5140/

“RAPID MODELING OF COMPOUND FLOODING ACROSS BROAD COASTAL REGIONS AND THE NECESSITY TO INCLUDE RAINFALL DRIVEN PROCESSES: A CASE STUDY OF HURRICANE FLORENCE (2018)”. Leijnse et al. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1142/9789811275135_0235

“FORECASTING HURRICANE IMPACTS ON COASTS USING COASTAL STORM MODELING SYSTEM (COSMOS)”. Van Dongeren et al. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1142/9789811275135_0242

“An Integrated Assessment of Climate Change Impacts and Implications on Bonaire”. Van Oosterhout (2023). https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s41885-023-00127-z

“Towards FAIR hydrological modeling with HydroMT”. Boisgontier et al. (2023) .EGU General Assembly 2023, Vienna, Austria, 24–28 Apr 2023, EGU23-13770, https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-egu23-13770.

“Deriving a parametrization for estimating nearshore infragravity wave energy for scaling up wave-resolving flood hazard modelling”. Leijnse et al. (2023). 17th International Workshop on Wave Hindcasting and Forecasting.

“Wave effects in a rapid compound flood model”. van Ormondt et al. (2023). 17th International Workshop on Wave Hindcasting and Forecasting.

“Dynamic Modeling of Coastal Compound Flooding Hazards Due to Tides, Extratropical Storms, Waves, and Sea-Level Rise: A Case Study in the Salish Sea, Washington (USA)”. Nederhoff et al. (2024). https://doi.org/10.3390/w16020346

“Accounting for Uncertainties in Forecasting Tropical Cyclone-Induced Compound Flooding”. Nederhoff et al. (2024). https://gmd.copernicus.org/articles/17/1789/2024/

“Estimating nearshore infragravity wave conditions at large spatial scales”. Leijnse et al. (2024). doi: 10.3389/fmars.2024.1355095

More information regarding recent advancements with subgrid features can be seen in this online poster: https://agu2020fallmeeting-agu.ipostersessions.com/Default.aspx?s=9C-05-18-CF-F1-2B-17-F0-7A-21-93-E6-13-AE-F3-24

Leijnse et al. (2020)

More information regarding recent comparisons using SFINCS to model waves can be seen in this online poster: https://agu2020fallmeeting-agu.ipostersessions.com/?s=30-38-5A-0C-8E-22-C8-84-CC-46-3C-95-18-80-C2-76&token=5r05NKrASrFrnkybTgXa4Y_XvgfV233Dazers0d2Zzo

Lasserre et al. (2020)